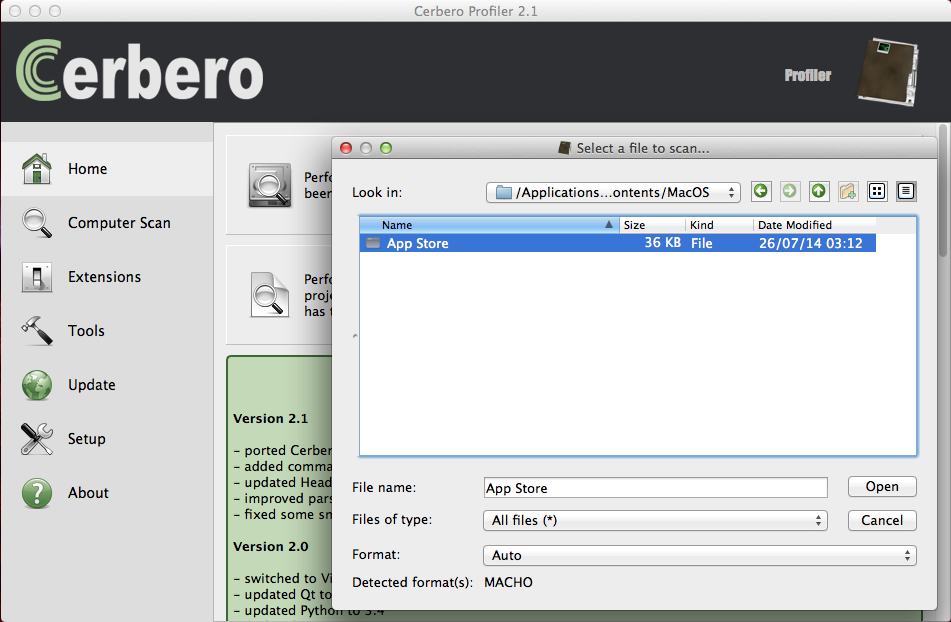

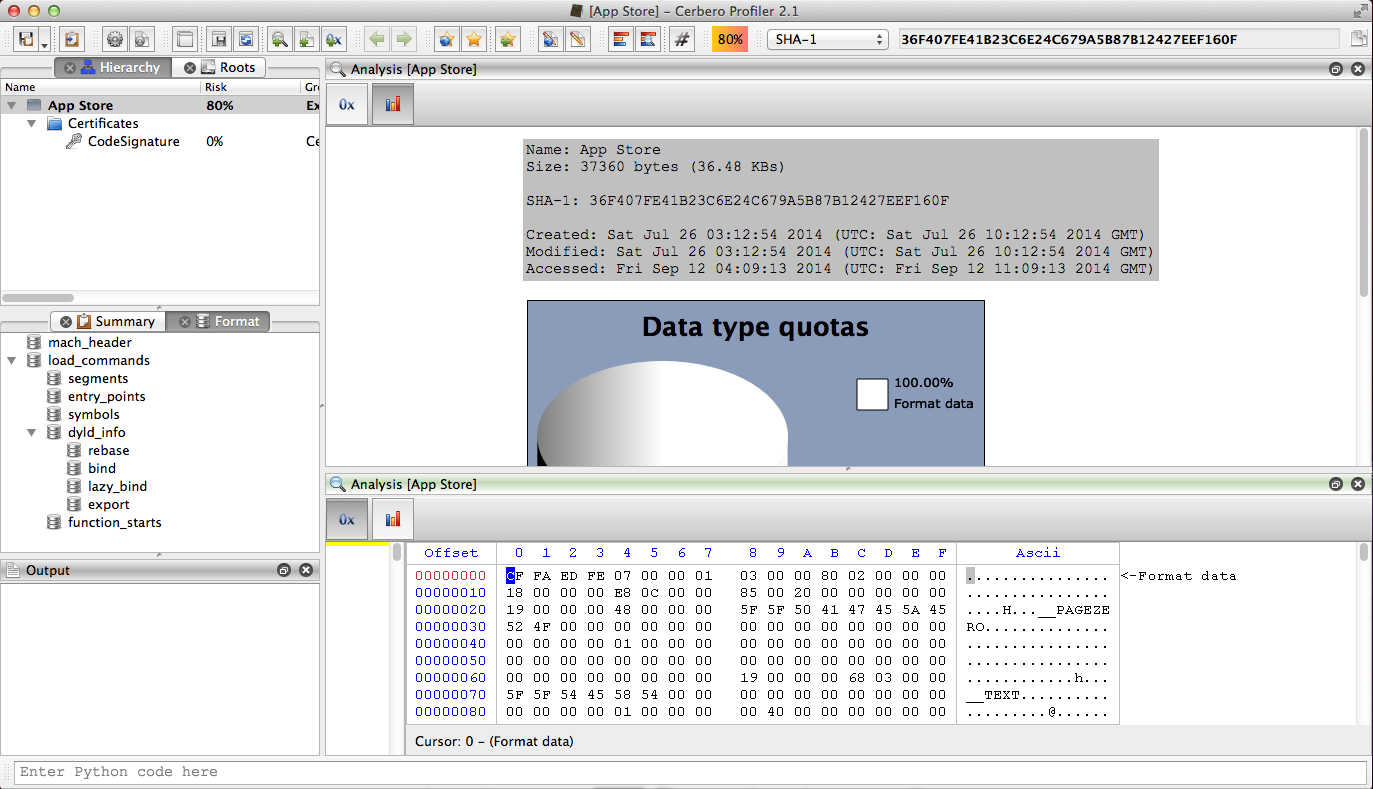

The upcoming 2.1 version of Profiler adds support for command-line scripting. This is extremely useful as it enables users to create small (or big) utilities using the SDK and also to integrate those utilities in their existing tool-chain.

The syntax to run a script from command-line is the following:

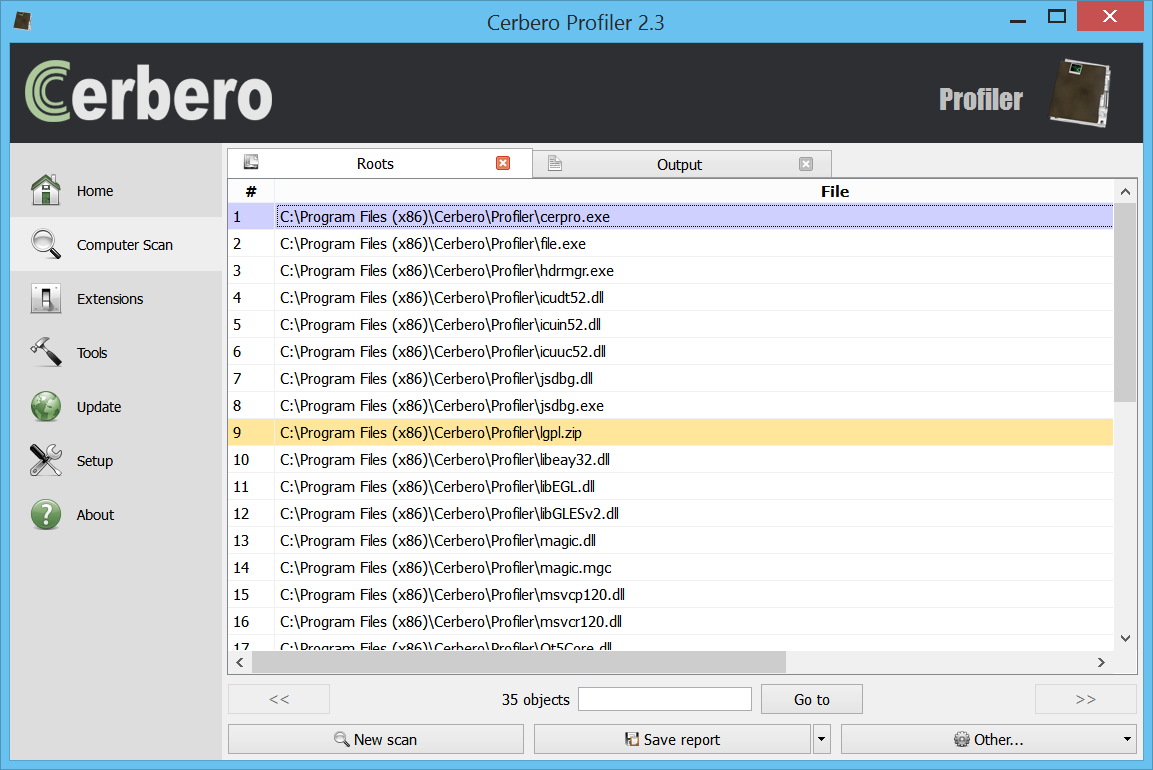

cerpro.exe -r foo.py

If we want to run a specific function inside a script, the syntax is:

cerpro.exe -r foo.py:bar

This calls the function ‘bar’ inside the script ‘foo.py’.

Everything following the script/function is passed on as argument to the script/function itself.

cerpro.exe -r foo.py these "are arguments" for the script

When no function is specified, the arguments can be retrieved from sys.argv.

import sys

print(sys.argv)

For the command-line above the output would be:

['script/path/foo.py', 'these', 'are arguments', 'for', 'the', 'script']

When a function is specified, the number of arguments are passed on to the function directly:

# cerpro.exe -r foo.py:sum 1 2

def sum(a, b):

print(int(a) + int(b))

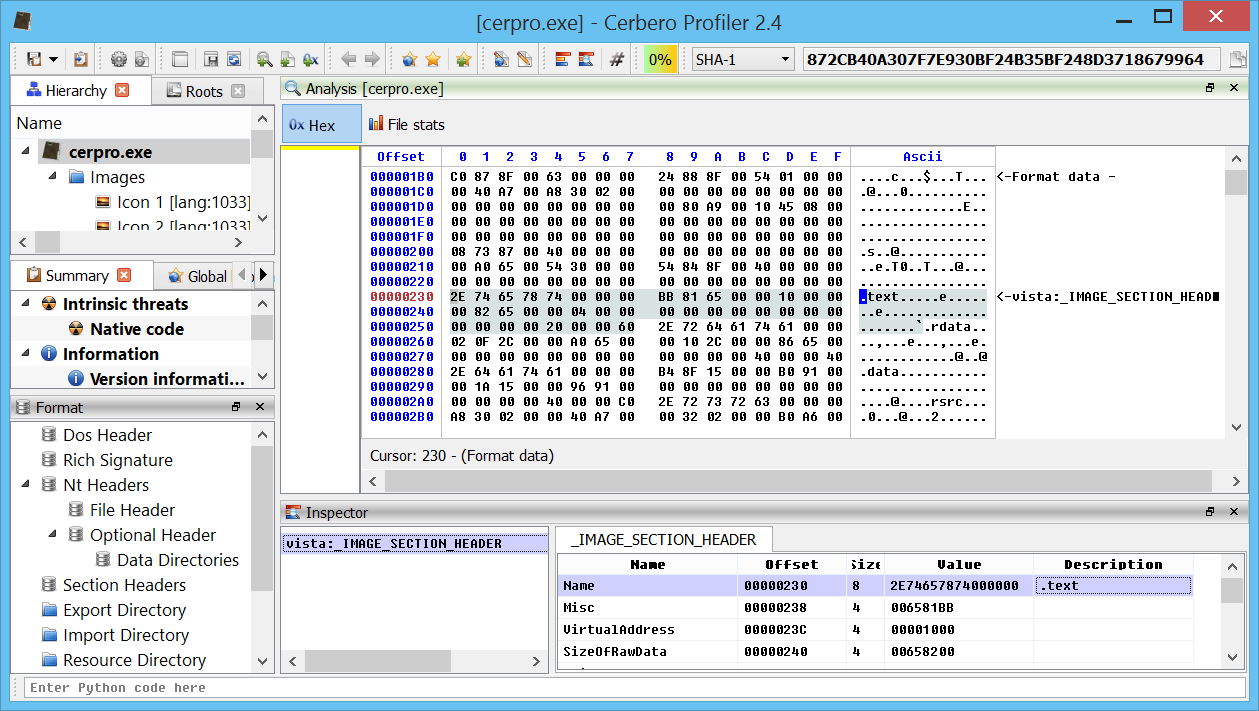

If you actually try one of these examples, you’ll notice that Profiler will open its main window, focus the output view and you’ll see the output of the Python print functions in there. The reason for this behaviour is that the command-line support also allows us to instrument the UI from command-line. If we want to have a real console behaviour, we must also specify the ‘-c’ parameter. Remember we must specify it before the ‘-r’ one as otherwise it will be consumed as an argument for the script.

cerpro.exe -c -r foo.py:sum 1 2

However, on Windows you won’t get any output in the console. The reason for that is that on Windows applications can be either console or graphical ones. The type is specified statically in the PE format and the system acts accordingly. There are some dirty tricks which allow to attach to the parent’s console or to allocate a new one, but neither of those are free of glitches. We might come up with a solution for this in the future, but as for now if you need output in console mode on Windows, you’ll have to use another way (e.g. write to file). Of course, you can also use a message box.

from Pro.Core improt *

proCoreContext().msgBox(MBIconInfo, "hello world!")

But a message box in a console application usually defies the purpose of a console application. Again, this issue affects only Windows.

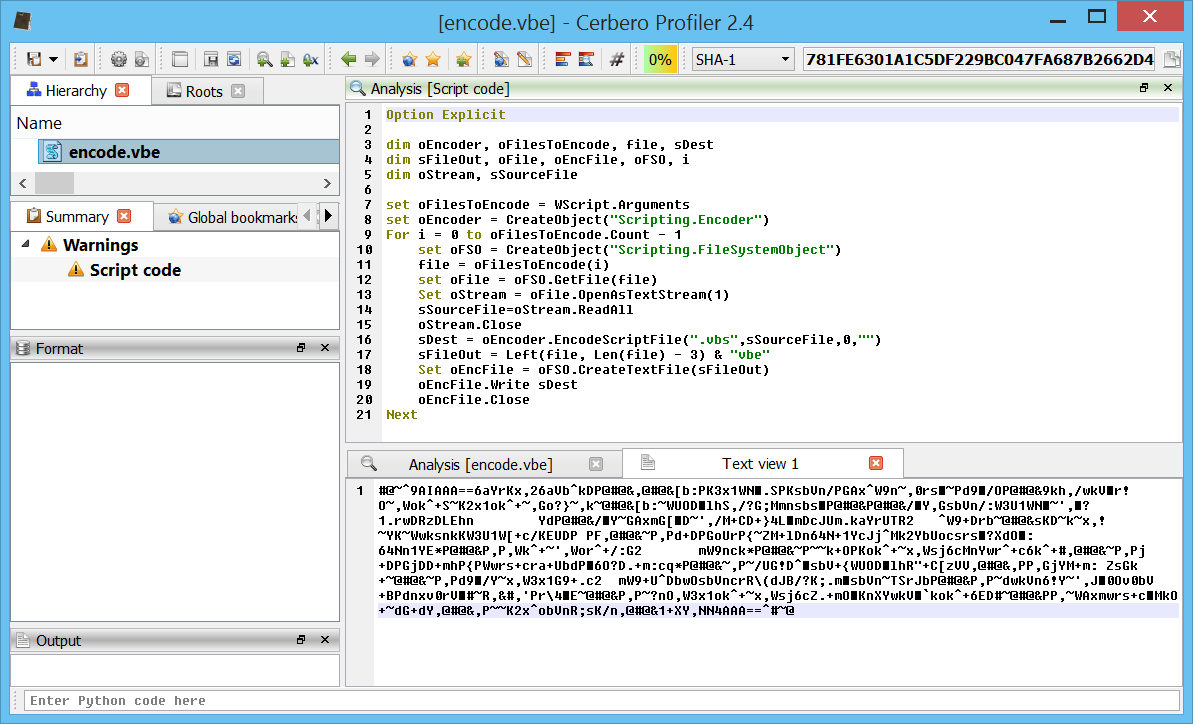

So, let’s write a small sample utility. Let’s say we want to print out all the import descriptor module names in a PE. Here’s the code:

from Pro.Core import *

from Pro.PE import *

def printImports(fname):

c = createContainerFromFile(fname)

pe = PEObject()

if not pe.Load(c):

return

it = pe.ImportDescriptors().iterator()

while it.hasNext():

descr = it.next()

offs = pe.RvaToOffset(descr.Num("Name"))

name, ret = pe.ReadUInt8String(offs, 200)

if ret:

print(name.decode("ascii")) Running the code above with the following command line:

cerpro.exe -r pestuff.py:printImports C:\Windows\regedit.exe

Produces the following output:

ADVAPI32.dll

KERNEL32.dll

GDI32.dll

USER32.dll

msvcrt.dll

api-ms-win-core-path-l1-1-0.dll

SHLWAPI.dll

COMCTL32.dll

COMDLG32.dll

SHELL32.dll

AUTHZ.dll

ACLUI.dll

ole32.dll

ulib.dll

clb.dll

ntdll.dll

UxTheme.dll

Of course, this is not a very useful utility. But it’s just an example. It’s also possible to create utilities which modify files. There are countless utilities which can be easily written.

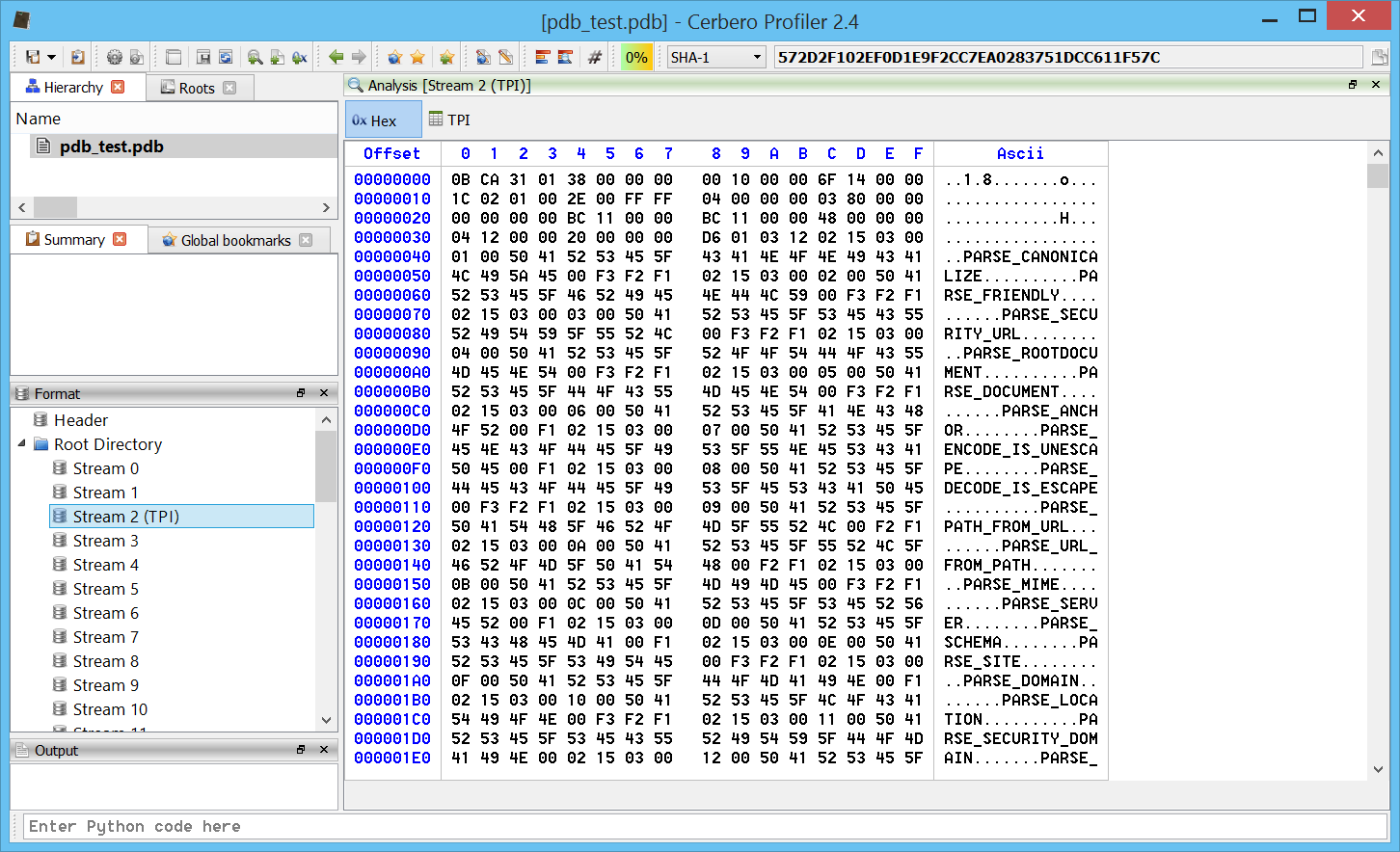

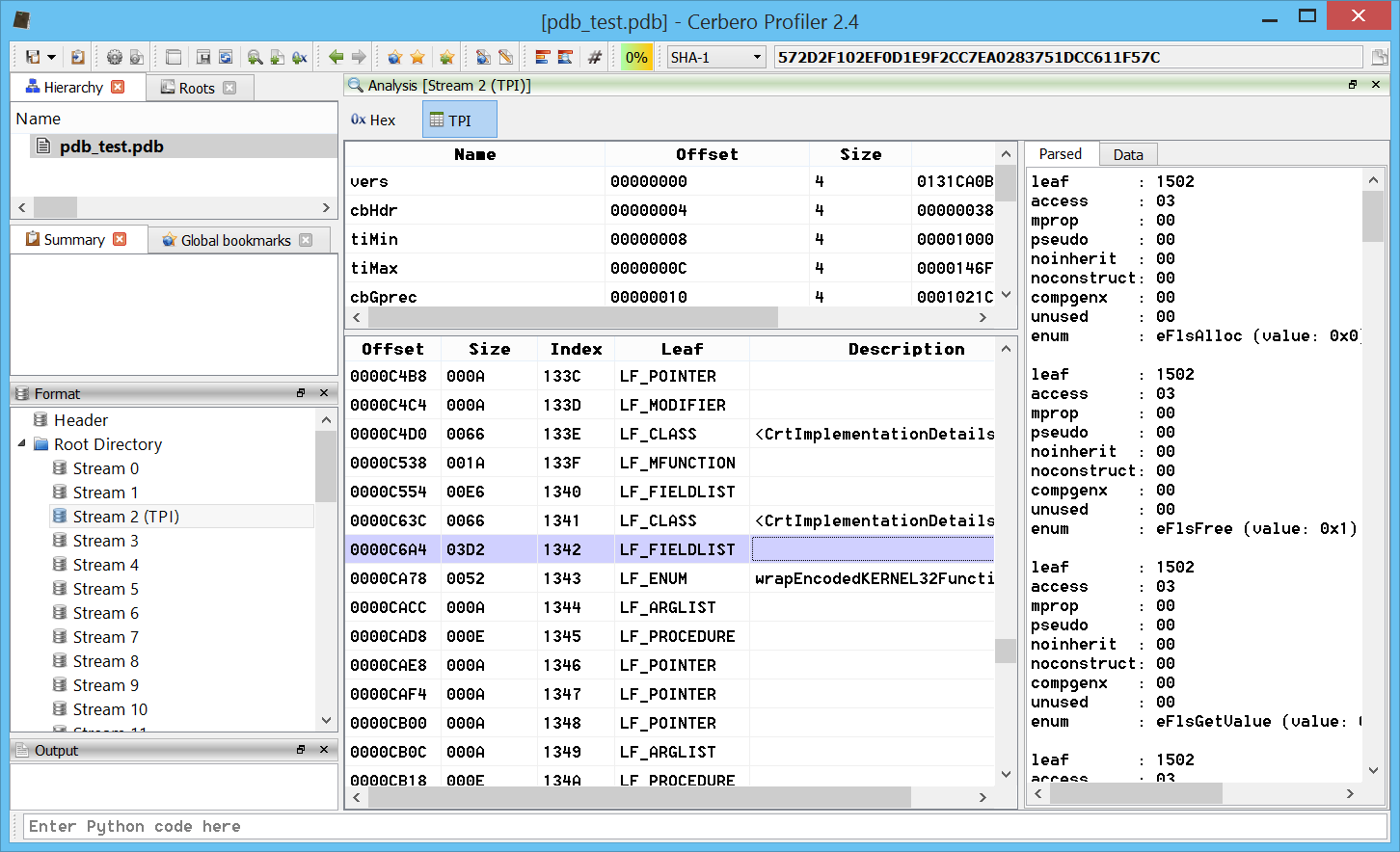

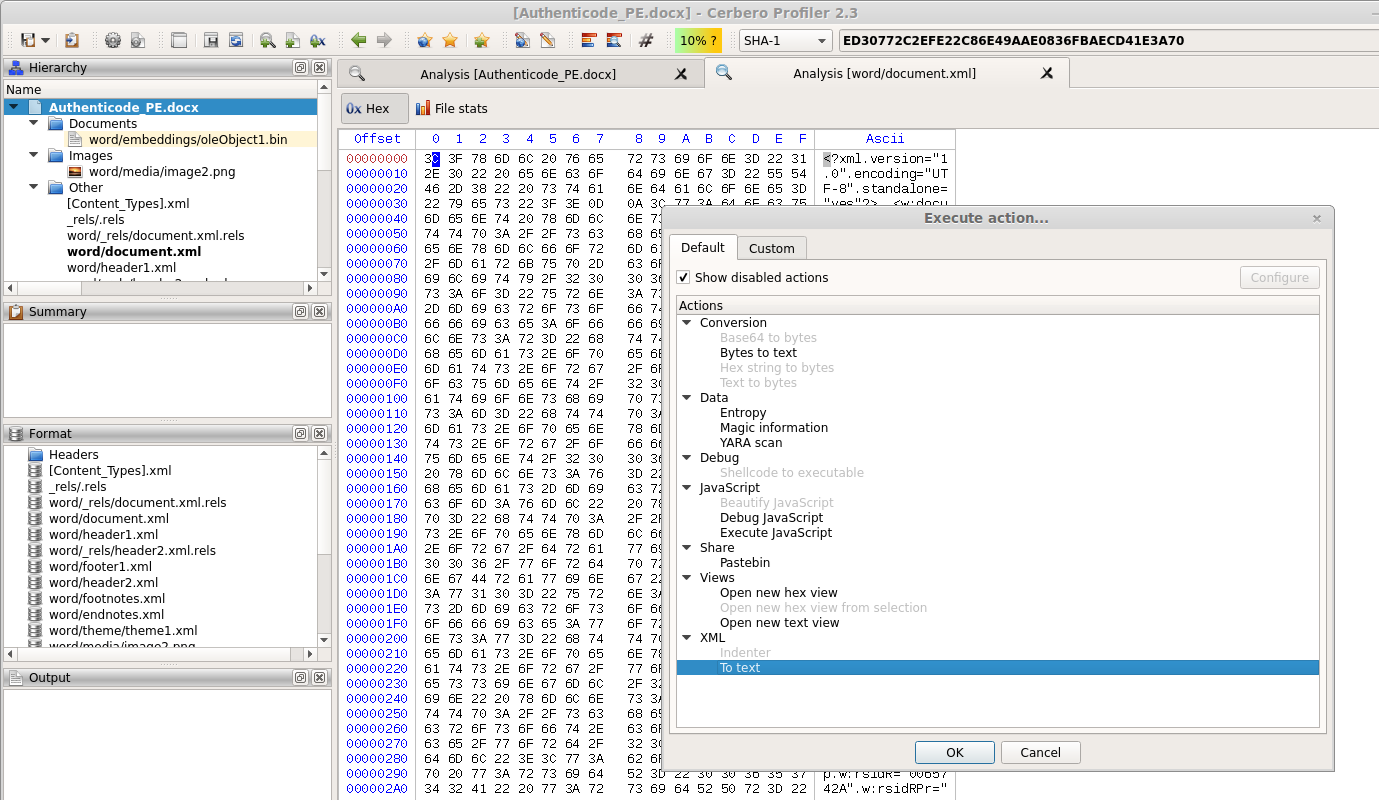

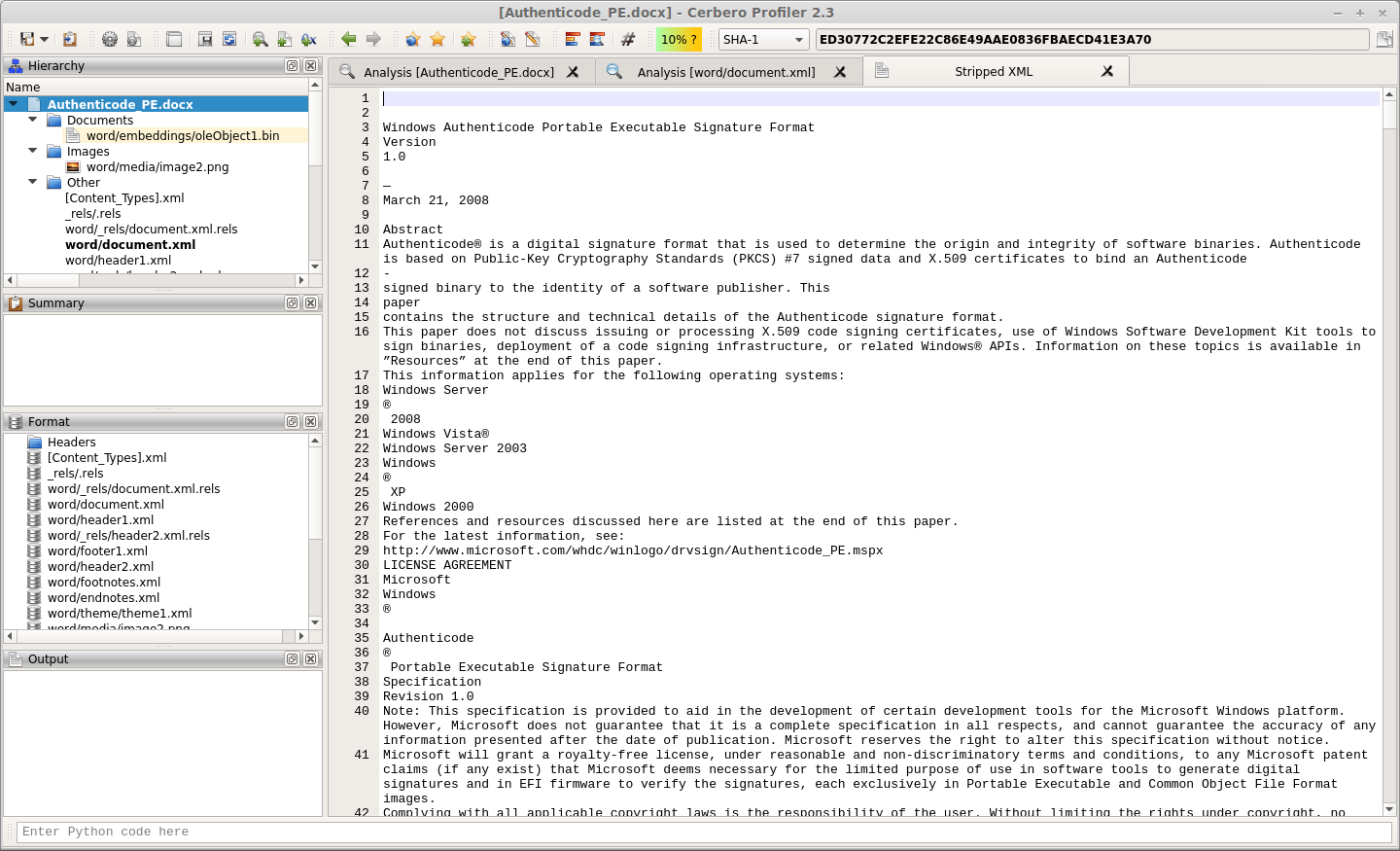

Another important part of the command-line support is the capability to register logic providers on the fly. Which means we can force a custom scan logic from the command-line.

from Pro.Core import *

import sys

ctx = proCoreContext()

def init():

ctx.getSystem().addFile(sys.argv[1])

return True

def end(ud):

pass

def scanning(sp, ud):

pass

def scanned(sp, ud):

pass

def rload():

ctx.unregisterLogicProvider("test_logic")

ctx.registerLogicProvider("test_logic", init, end, scanning, scanned, rload)

ctx.startScan("test_logic") This script scans a single file given to it as argument. All callbacks, aside from init, are optional (they default to None).

That’s all! Expect the new release soon along with an additional supported platform. 🙂